Boingboing blogs from… Pretoria

Co-researching drought in South Africa

by Angie Hart, Boingboinger

Angie tuning in from Pretoria, South Africa. A whole group of different people from the UK and South Africa, including the University of Pretoria, University of Brighton, Boingboing, and also Khulisa community organisation, have been lucky enough to win a research bid. We’re funded from a pot of research money aimed at getting researchers to understand and address major challenges affecting countries in the global south. Our project’s on Patterns of Resilience to Drought, exploring community resilience to drought in South Africa from loads of different angles. Right now as I write this in South Africa, we’re focusing on the perspectives of community members who are co-researchers on the project.

The Natural Environment Research Council from the UK is leading the management of this funding pot, but other UK Research Councils are contributing to it too. Together we’re exploring the issue of resilience to drought from all different angles, historical, cultural, social and economic. We’ve also got a strong arts perspective running through the project – in the early days of the project we have been using arts based methods in what might be seen as an instrumental and extractive way. Later on we are moving more to artists leading us all in developing some art events or artifacts that will communicate knowledge as knowledge itself. We’re hoping community members will want to co-produce artistic expressions of how drought affects them and incorporate strategies to address this. Crucially, our hope is that young people from affected communities will be in the driving seat of what gets communicated to others about this. And we’re hoping that our findings will feed into drought policies in South Africa.

Boingboingers brimming with excitement. We’re in a very cool classroom at the University of Pretoria, getting started with the group we are going to be with for the next few days. We’ll be working together at the University and then afterwards in a rural community. We’re with South African project lead, Prof Linda Theron, and colleagues from University of Pretoria, including our fabulous Project Manager, Mosna Khaile, who is also one of Linda’s postgraduate students. They have gathered together a group of postgraduate students studying to be educational psychologists. The students have got involved in our project and are all doing their own individual research projects that are feeding into it. The students are doing this as part of their course and they are very motivated. Today we are on a co-training mission. ‘We’ being all the South African colleagues I just mentioned, and Angie, who is the overall boss of the project (known technically as the Principal Investigator). Two other UK team members, young co-researchers Lisa and Simon, are there too, and Scott from Boingboing is our technical back up and is also supporting Lisa and Simon.

Collectively we are working on arts-based approaches to understanding and combating drought in Leandra, a small township in South Africa. The idea is that we co-train the students and then they will facilitate the local young co-researchers in Leandra to come up with collective perspectives on drought. After that they will work with community elders to deepen understandings of resilience to drought. Some of the things we want to get to are: How do you know when there is a drought? What do you see? What do you smell? What do you feel? How do you manage to be ok when there is a drought?

We cover various different arts-based methods. The point gets made many times that it’s not about how good your art is. It’s about what it means and what it evokes. Hmmm, I know people always say this in these kinds of exercises, but I still catch proper artist facilitators looking at my creations with pity when they think I’m not staring in their direction.

One of our co-researchers, Dr Motlalepule Mampane, kicks us off with a lovely demonstration of how we might use small stones in a figurative way to represent people to elicit stories about how families deal with drought. She is a beautiful story teller and I was mesmerised by the tale she told of a family caught in a dilemma of whether or not to share their provisions with another family who were on the brink of starvation.

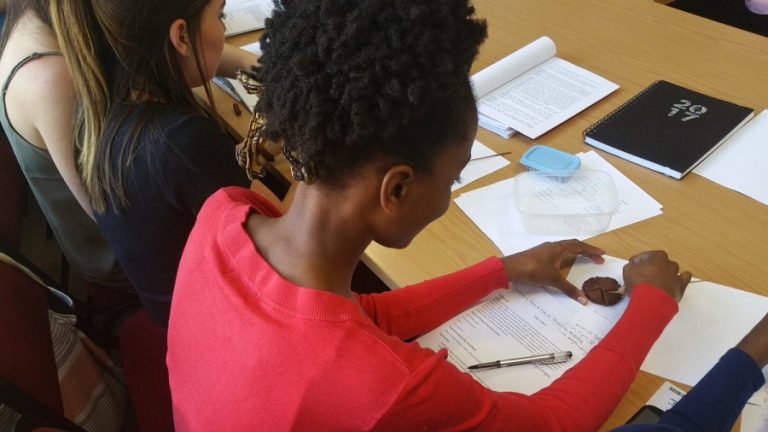

Here’s what Linda T did to teach us one approach. She asks the students and our co-researchers to get into small groups. She wants them to make a clay model or drawing in 10 minutes. They need to represent as a group, the answer to the question, ‘How do you know when there’s a drought?’ The groups come out with answers like: The animals are really thin and so are the people. Children have big tummies, skeletal hands and are very sad. The food prices go up. We have a clinic with a long line because diseases spread and people get sick. After that exercise, Linda tells us that they need to ask their group, ‘How do you know when a drought is serious?’ This wasn’t a question that they as academics dreamed up. It was a question that came out very strongly when Mosna and Linda visited the community whilst setting up the project.

Linda’s now leading them in a good discussion about how not to ask leading questions. Also, we’re discussing the ethics of recording what they say and do, and the need to keep on asking for consent, not just as a one off at the beginning of the day. Reflections on how well the exercise went and how useful it is for co-researching drought with young people from the community. For one student, it was a safe activity that was fun to do, even though it was dealing with a traumatic event. Boingboing’s Lisa said she wanted everyone to draw if they wanted to, rather than just one person doing it on behalf of the group.

We reflected together on what we will do if this activity does actually trigger someone getting very upset. Some of the young people may have had traumatic experiences in their families related to drought, so we really need to be careful that we don’t re-traumatise anyone. Three psychologists are part of the leadership of our group, so that’s one route to supporting anybody individually who needs it, should that happen. The students who are going to facilitate the groups know that they should call on one of their tutors if somebody in their group needs extra input. Then they can all think together about how best to support the person. There might be a need for some formal psychological support, or it may be more appropriate to provide peer support or involvement of the local community organisation lead.

Now we’re going on to discuss developing a timeline with the co-researchers. We want to find out when they last experienced a drought. That would be the beginning of the time line. In this timeline we are going to put all the events that they experienced as a result of the drought. These could be positive or negative experiences. Linda explains about another part of our project. The work being done by Dave Nash, Claire Kelso and Phil Ashworth, on examining historical drought records from the government archive for the area. We then want to use that information and compare with what the young people say tomorrow about droughts they have experienced. One of the students said that she’d used a technique that asked people to walk the timeline. Standing up and talking in different points before they write it out, they can walk into their past and into their future. Very flexible.

Some of the things we have been pondering: On the first day, young people are knowledge producers. So are they co-researchers then, or not? How are we going to be thinking about them and how will they think of themselves? When is a researcher not a researcher?

Body mapping is the next activity we are practising. A few students are lying on large pieces of paper with others drawing around them. You now say to your group, ‘Do you see how your body is mapped onto this piece of paper? I’d like you to show me now on your body, if you think back to your timeline, in your body how did this feel? How did you experience the drought?’ First they begin to decorate themselves. Clothing and hairstyles. Leave them to do that first, but then ask them to, ‘Show where you felt it in your body. What were the thoughts? What did you have to do?’ It may be that they show their hands carrying water. Or they may show their hearts all sad. We also have to move it to the resilience perspective. ‘So how did you cope? How did you manage to get through the drought and be survivors of it? When there was a drought, what helped you to stay healthy in your minds, in your heart and in your body?’

Prof Liesel Ebersöhn emphasises that the body maps are being used here as ways to elicit conversation. So she suggests the students say things like, ‘Tell me more about what you’ve drawn there…’ The students will have to manage their time very carefully so they get time to take photos and record all the information the young people give us. There’s only an hour for each activity so we have to work very hard to do the activity and to record it.

Following a swift lunch, during which we pondered the fact that all the students here are female Ed Psych students, we’re talking about using trays of sand in our research. Liesel leads us in a demonstration of why community co-researchers might find that medium useful as a vehicle to talk about their drought experiences. Small figurines can be used in the sand to represent people, animals, houses etc. Gets the conversation flowing. But it wasn’t practical to get the sand trays out in the classroom so we’ll have to wait until we do that tomorrow for a picture of that.

Our community partners in South Africa have said that young people in their community would not use the word ‘resilience’ at all, and wouldn’t understand what was meant by it. So Linda and Mosna worked with our community partners to come up with an understandable way of talking about it. They wanted community co-researchers to speak to a definition of resilience that captures both their individual actions towards supporting their own resilience, and what resources they might get from elsewhere. So, after much deliberating, the questions the students and our young people will be exploring with Leandra community co-researchers tomorrow is, ‘What does it mean for a young person to be ‘ok’ when there is a drought?’ And they will then ask, ‘What or who makes it possible for young people to be ‘ok’ when there is drought?’ Can’t wait to hear the discussion.

Next up is Mosna leading us in a singing and poetry activity. Co-researchers tomorrow might be up for making up a song about how the day went for them, so the students and our young co-researchers are having a practice. The idea is to do it in a group if they fancy. Gets a nice bit of cohesion going. They are having such fun. Great activity for the postprandial slot.

After a lively bit of singing, we go on to think about the next day’s research we will be doing in Leandra. Young co-researchers will be trained up in basic research skills and they will then be interviewing elders (over 40) in their community about their perspectives on drought. Between when we leave on Wednesday and when we come back in June, those young co-researchers have the opportunity to find an adult in their community they feel comfortable with. They’ll be interviewing them about drought. We’ll be giving the young people notebooks and hoping that they will record the elders’ perspectives in them. Let’s hope they do this. If it were me I’d probably lose my notebook and my own experience of supporting co-researchers to keep notes like this hasn’t always been that successful.

There’s been a bit of a discussion about the languages that will be used in the community. There may be quite a few different languages spoken and the Masters’ students can speak some of the languages that will be spoken tomorrow. We have budgeted for translation, so people should feel free to speak in whatever language they like. Our young co-researchers from the UK will be struggling a bit there, but we’ll all get to hear what people have said eventually after translation.

A discussion that I’m very familiar with gets started on ethics. How are local people going to get their heads around the consent form and all the blurb on it? The students are going to take the consent forms to bed with them tonight so they can really help participants/co-researchers understand them.

Our Lisa asks a good question about practicalities. Will the young co-researchers know what financial recompense they are getting for being involved in the project? Linda and Mosna explain that that’s already been dealt with. They get to choose which shop they want vouchers for. Vouchers are going to their families, not to individual co-researchers. A lot of work has gone into deciding this in collaboration with the local community organisation.

We end our day with a great discussion of the nature of co-researching. Someone said that our project is about supporting young people to become custodians of their own knowledge so that they can advocate for action in different ways. Very deep. I can’t recall who said that. Suffice it to say it wasn’t me. Can’t wait for tomorrow when we’ll be working in Leandra and I’ll get a chance to see the co-researchers in action. Exciting stuff.