Academic Resilience key points

• Good educational outcomes despite adversity

• We can spot the impact of academic resilience through individuals doing better than we might have expected

• Promoting academic resilience will lead to better behaviour and results for disadvantaged pupils.

Academic resilience means students achieving good educational outcomes despite adversity. For schools, promoting it involves strategic planning and detailed practice involving the whole school community to help vulnerable young people do better than their circumstances might have predicted.

With this way of working, schools can help not only to beat the odds for individual pupils, but also with changing the odds for disadvantaged pupils across the board.

Sounds easy right? Well, we know if it were simple, everyone would have already achieved it and you could be doing something else right now instead of reading this. This resource will give you a hand with putting the theory into practice.

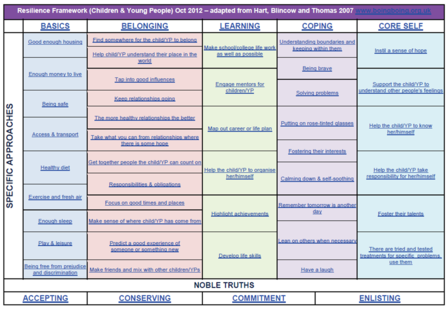

• View the Resilience Framework (pdf) in full size

• Download an Interactive Resilience Framework (pdf) with supporting information

The Resilient Classroom: Want a resource so you can get on with promoting resilience in PSHE or tutor group? Try our Resilient Classroom (pdf) resource for bite size, downloadable activities for 20 min sessions.

Have a look at how one school developed the Framework into an individual child assessment tool using the headings (Eleanor Smith School, Newham).

• Pictorial Framework – Version 1

• Pictorial Framework – Version 2

How can we spot academic resilience?

These kinds of conversations would be going on in your school community if your school has done well at increasing pupils’ academic resilience:

“Remember when George Smith left school and was offered that plumbing apprenticeship and we couldn’t believe it? Apparently he has stuck it out and is doing well. Even his mum used to say he was destined for prison!” – Deputy Head

“Can’t believe that Kuljinder is doing so well now. She left school with five GCSEs and has gone to college to do ‘A’ Levels. In Year 7 she got excluded and her mum was in a psychiatric hospital. Unbelievable.” – Key Stage Four teacher

“Carl Jones was one of the lads painting the canteen this weekend as part of the alternative education programme. He was telling me about his previous exclusions and the kinds of trouble he used to get in to at weekends. He seems determined to do better at school now he can see a future for himself.” – School caretaker

Of course it might not be your personal responsibility to make this all happen. But we’d like to convince you that whoever you are in the school community you have a valuable role to play in achieving academic resilience. Everyone in the school community can contribute… and sometimes new roles in school can help fill some gaps- the kinds of things that others haven’t got time or skills to do. Have a look at the film below for some ideas from some other schools.

And basically the theme here is ‘so and so did better than we expected’. Imagine this kind of ‘positive gossip’ resounding round the staff room? Some more experienced teachers have told us that our approach reminds them of the old days when teachers were encouraged to get involved in other aspects of a pupil’s life. Young and old teachers have told us this:

“Helping those pupils who have lots of barriers to overcome is why I went in to teaching in the first place.”

It’s not rocket science. What we are saying is that positive progress for pupils facing adversity comes in many forms – building their resilience will help ensure that progress. Believing in potential is what teachers and others in school do so well – the school just needs to find ways to support staff to act on that belief.

What does the evidence tell us?

Some children are simply born brainy and despite the most difficult circumstances, they will do well in school. (For example Oprah Winfrey suffered all kinds of childhood horrors, but studied hard at school and went to university too). In fact for some brainy children, school can be a refuge and a much calmer, safer place than home.

We know that children with certain advantages are more likely to do well at school – intelligence, height, looks, etc plus stable home life, educated parents, decent housing – these kinds of factors are known to increase the likelihood of academic attainment.

At the same time, there are many risk factors which make a child less likely to achieve. There are certain issues that keep cropping up in the research findings about what can work in building resilience in vulnerable children and young people, including:

- At least one trusted adult, with regular access over time, who lets the pupils they ‘hold in mind’ know that they care

- Preparedness and capacity to help with basics, i.e. food, clothing, transport, and even housing

- Safe spaces – quiet, safe spaces for pupils who wish to retreat from ‘busy’ school life

- Making sure disadvantaged pupils actually access activities, hobbies and sports

- Help to map out a sense of future (hope and aspirations) and developing life skills

- Help to develop and practice problem-solving approaches at every opportunity

- Help for pupils to calm down and manage their feelings

- Support to help others e.g. volunteering, peer mentoring.

- Opportunities for all staff, pupils and parents to learn about resilience

- Staff treat each other with care and respect, modelling the behaviour they expect from pupils.

How will promoting academic resilience help our school achieve better results?

Building resilience involves doing a whole bundle of things that don’t always happen in the classroom. We know from years of research that supporting pupils to build resilience improves their academic results.

But why is this? Why is it that say, helping a pupil with challenging behaviour join the Woodcraft Folk and take part in their activities each week, would have a knock on effect on academic achievement?

The same question could be asked again of this situation. Imagine a child being asked how their poorly mum was doing by a kindly dinner lady. Imagine that child feeling cared for as a result of that conversation. All these kinds of processes help pupils settle down, concentrate and feel better about themselves.

All of which, as anybody in the school community will know, will have an impact on learning and educational achievement.

Improved behaviour and attendance at school are all part of that. Of course there are longer term benefits – some of the processes and practices involved in resilience building will give pupils access to opportunities that they would never have had before.

For example, suppose the Woodcraft leader runs a fish and chip shop and that pupil who settled in her club ended up getting work experience there for a few weeks. Who knows, right now he might be running his very own chip shop.

Even longer term benefits for children, families and wider society include better physical health, increased life expectancy and better long term mental health for the most vulnerable members of society. What’s not to like?

Some might say that all this boils down to us being kinder to pupils, but there really is more to resilience promotion than just that. It involves using tried and tested ideas to help support vulnerable pupils to genuinely close the gap.

It also involves leadership and commitment. Check out what these school leaders say about their expectations of the whole school community in making sure no child is left behind.

In our experience having an evidence-based resilience framework to help plan and support what you do – whether you are the head teacher or a parent – can make you stay on track and keep going especially when the going gets tough.

And let’s face it, achieving academic resilience for the most vulnerable pupils isn’t plain sailing, however kind you are.